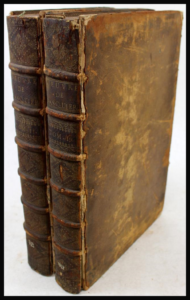

While thinking about this month’s topic I was browsing the Bibliography section of our stacks and spied the set Repertorium Bibliographicum by Ludwig Hain. As the history and development of printing during the Early Modern Period is one of the specialties of our library research I thought that this would be a great item to highlight. Repertorium Bibliographicum is one of the indispensable works for the study of early printed books during the incunabula period. Even though it is more than 180 years old, and there are newer reference sources, it is still a basic resource for the study of books printed before 1500.

Looking to add some background on Mr. Hain I quickly found that there is very little recorded about his life. Born Ludwig Friedrich Theodor Hain in 1781, he worked privately as a bibliographer in the later part of his life while living in Munich (check out the

WorldCat entry for Hain). It was during this latter part of this life that he researched and published his

Repertorium Bibliographicum : in quo libri omnes ab arte typographica inventa usque ad annum MD. typis expressi, ordine alphabetico vel simpliciter enumerantur vel adcuratius recensentur. Hain died in 1836 before finishing his research. The first edition, a

four volumes in two set, was printed in Stuttgart from 1826-1838 (published in 1826, 1827, 1831 & 1838). It is noted that the entries compiled after his death, do not come up to the standard Hain maintained. Since then

Repertorium Bibliographicum has gone through many reprintings and editions. Given the importance of his work as an editor and bibliographer, the number times the work has been reprinted, and the value it has brought to bibliography, it is quite surprising that there is so little biographical information on his life.

Repertorium Bibliographicum

Arranged alphabetically by author, Hain cataloged some 16,299 incunabula. Each incunabulum is numbered and includes detailed descriptive information on the specific copy of the book that Hain was cataloging. Many incunabula are available from only a single copy or even a fragment of a book. Even where there are multiple copies of a book there can be significant variations between individual specimens’ due to the printing techniques of the time. Hain personally reviewed the vast majority of these books, more than 13,000 volumes!

Hain was the first bibliographer to create a specific method for cataloging incunabula. While there were earlier bibliographers who published about the books of this period, their catalogs of incunabula did not follow any consistent structure. Hain, with his innovative methodology, brought order to the field of study.

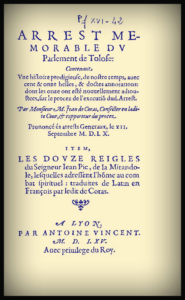

As can be seen in our example, Hain’s entries are cryptic. C.C. McCulloch notes, in his article On Incunabula 1, for books printed after 1500 cataloging is focused on the title page. For works published before 1500 title pages are rare or a title page was never printed. Information about the author or publisher was often omitted entirely. If recorded, details about the author, publisher, date and place of publication where generally included in the colophon at the end of the text. The last page of a text block is very likely to be damaged or lost. Also, bibliographical information might was not always deemed to be important enough to be recorded by the printer or publisher. To compound the problem when information is provided in the text it could be inaccurate. Again, it is highly likely that the reasons for these lacunae are primarily due to the book production and binding practices that were inherited from the manuscript trade.

For fifteenth century books Hain established the following rules:

The cataloger provides the author and the title (or if the author’s name is not known, the title alone); the place of publication, the printer’s name, the date and the size. Next is copied:

exactly and literally, including the abbreviations used, the first lines of the first leaf, marking the end of each line by an upright stroke. [You can see this in our example as a double vertical bar ‖ .] 2

Additional bibliographic information is collected, such as a description of the beginning of signatures and registration marks, and, if available, an exact copy of the colophon. When available, the number of leaves, size of page, number of columns, number of lines on the page, stop words, and any other information about the print production of the work is added to the record. Many other characteristics of the copy are included so that the catalog record can be quite detailed and provide enough information to identify a specific copy of a work.

In the sample page above, books that Hain physically reviewed are preceded by an asterisk. Where Hain did not see the book, the catalog number is not preceded by the asterisk and there is only a brief description.

The legacy of Hain and the Repertorium Bibliographicum

While other catalogers and historians of incunabula preceded Hain, his methodology has been followed by later researchers. Nearly fifty years elapsed after his death until the topic was revisited. As newly found incunabula were discovered and errors were uncovered, updates to entries became necessary, where Hain only had second hand information further information was uncovered. By 1900 it was estimated that there were more than 40,000 incunabula produced by the publishers and printers of the fifteenth century. Obviously supplements and revisions were in order. Successive printed works include:

- Copinger, Walter A. Supplement to Hain’s Repertorium Bibliographicum. Or, Collections Toward a New Edition of that Work. In two parts. London, H. Sotheran and co., 1895-1902. 2 vols. Contents: pt. 1. Nearly 7000 corrections of and additions to the collations of works described by Hain. 1895–pt. 2. Nearly 6000 volumes not referred to by Hain: v. 1. Abano-Ovidius. 1898. v. 2. Pablo-Zutphania. With addenda to parts I. and II. and Index by Konrad Burger. 1902.

- Reichling, Dietrich. Appendices ad Hainii-Copingeri Repertorivm Bibliographicvm: Additiones et Emendations. Monachii: svmptibvs I. Rosenthal, 1905-11. 7 vols.

- Stillwell, Margaret Bingham. Incunabula and Americana, 1450-1800: A Key to Bibliographical Study. New York: Columbia University Press, 1931. Compiled by Margaret Stillwell, Librarian at Brown University.

- Berkowitz, David Sandler. Bibliotheca Bibliographica Incunabula: A Manual of Bibliographical Guides to Inventories of Printing, of Holdings, and of Reference Aids. With an Appendix of useful Information on the Place-Names and Dating… Waltham, Massachusetts, 1967.

The most notable descendants of Hain are found in the national and academic Online Census Databases and Catalogs of which the primary examples are:

We are all indebted to Hain and the Repertorium Bibliographicum.

The DLWA library has a number of these references, but here is the citation for the set that started tale.

Worldcat: Link

- Title: Repertorium bibliographicum: in quo libri omnes ab arte typographica inventa usque ad annum MD. typis expressi, ordine alphabetico vel simpliciter enumerantur vel adcuratius recensentur

- Publisher: Milano : Görlich, 1966

- Language: varies

- Setting: Incunabula of the Early Modern Period

- DLWA Call Number: Z240 .H15 1966

———————-

1. C. C. McCulloch, Jr. On incunabula. Publication: Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 1915 Jul; 5(1): 1-15.

2. Ibid. p. 9.