One of the earliest studies of mining and mineralogy is the book “De re Metallica : On the Nature of Metals” by Georgius Agricola (1484-1555) . 1 Agricola was born at a momentous time. Columbus returned from his exploration and the Renaissance was in its early stages. Just forty years earlier Gutenberg precipitated the printing revolution. With many close colleagues, like Erasmus, Agricola was one of the central players in the sixteenth century European Humanist milieu. He had lived in what is now the Czech Republic. Eventually he became a physician and soon thereafter the mayor of Kepmnicz in the eastern German Saxon states. These regions were some of the richest mineral producing areas of Europe and, even with his duties, he maintained a deep interest in the technology of mining.

“De re Metallica libri xii” was published in the year following Agricola’s death. Much of the delay was due to the large number of woodcut illustrations. Prior to its publication the only systematic study of mineralogy and mining was found in the writings of Roman classical writers, predominantly Pliney. Agricola wrote De re Metallica in Latin and in doing so he created many new terms in Latin where there had been no words existent to describe the process he was describing.

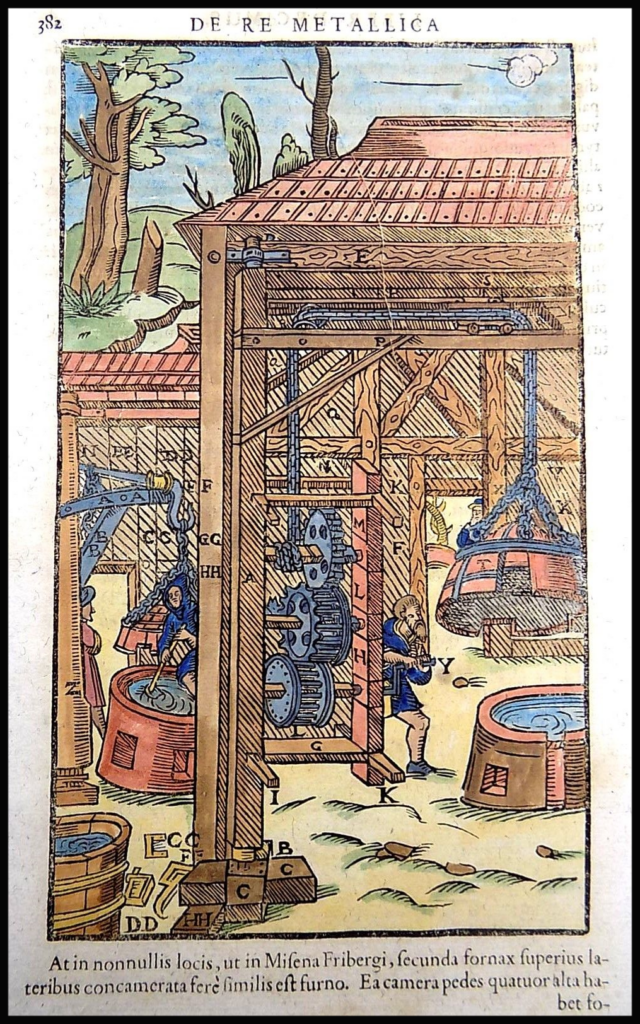

Our library if fortunate to have an illustrated page from Book X of a very early printing of this edition. Here Agricola illustrates a crane that is used to move the “dome” of a furnace. The text goes into great detail concerning the parts of the crane and the dimensions and use of each part. Combined with other text and illustrations, Book X focuses on the separation of silver and gold and lead from gold and silver.

“De re Metallica” became the most influential publication on these disciplines. Being published in Latin there was soon a need of translations into other languages. The first were in German and Italian. Of the German translation it is said:

The German translation was prepared by Philip Bechius, a Basel University Professor of Medicine and Philosophy. It is a wretched work, by one who knew nothing of the science, and who more especially had no appreciation of the peculiar Latin terms coined by Agricola, most of which he rendered literally. It is a sad commentary on his countrymen that no correct German translation exists. 2

There were plans for an English translation in the seventeenth century but there is no evidence that any was produced. It was not until the early 1900’s that another translation into English was undertaken. Starting in 1912 this translation was privately published and sold only through subscription by The Mining Magazine, London. Our library has the Dover Books reprint of this version.

The translators responsible for this version were Herbert Hoover and his wife Lou Henry Hoover, undertaking this commission while they were at Stanford University. Herbert Hoover was a mining engineer and Lou was a geologist as well as a Latin scholar. The Hoover translation is highly regarded. It was a masterful work that is undoubtedly the clearest rendition of Agricola’s text. It is also cited as a critical resource on the historical context of the progression of mineralogy and mining to the 1500’s. The Hoovers noted that the work was no longer useful for practical application as in the intervening time much progress had been made in the field of mining and mineralogy, but much of the value of this text is the accompanying scholarly research.

In the popular and simplified history of the United States, Herbert Hoover is often denigrated. It was his unfortunate responsibility to be President of the United States at the start of the Great Depression of the 19th century in 1929. He was also in the position to provide leadership in the aftermath of World War I. But in this book, there is one element of data to show that Herbert Hoover, along with Lou, had many more dimensions than they are given credit for. This is a cautionary tale – that we must not take popular opinion concerning a person and their work at face value. The Hoovers’ provided a valuable academic gift to the world on the study of ancient mineralogy and mining. What other valuable insights are we overlooking if we follow popular opinion, what might be found if, we, being careful to scrutinize our biases, learn what else they have to offer us.

—–

DLWA Call Number: TN617 .A25 1950

Worldcat: Link

- Title: Georgius Agricola De re metallica : tr. from the 1st Latin ed. of 1556, with biographical introduction, annotations and appendices upon the development of mining methods, metallurgical processes, geology, mineralogy & mining law, from the earliest times to the 16th century

- Language: English/Latin

- Setting: Book History

DLWA Call Number: AC1 TN617 .A25 1561

Worldcat: Link

-

- Title: Georgii Agricolae De re metallica libri xii, qvibu officia, instrumenta, machinae, ac omnnia deniq[ue] ad metalicam spectantia, non modo lucluentissime describuntur, sed & per effigies, sius locis insertas, aduenctis latinis, germanicisq[ue] appelationibus ita ob oculos ponuntur, et clarius tradi non possint. Evisdem De aaimantibvs svbterraneis liber, ab autore recognitus: cum indicibus deuersis quicqiuid in opere tractatum est pulchré demonstrantibus.

- Language: Latin

- Setting: Book History

—–

-

-

- We have used the English translation by the Hoovers, listed above, as a source for this post.

- ibid p.xv-xvi

-

–DLW