At the beginning of the Early Modern Period in Europe, roughly the mid 15th century to the late 18th century, readers were usually people of means or in an occupation that that required access to written materials. Both secular and religious centers like Universities and Monasteries were the hub of the book trade. Indeed, the advent of printing with movable type in the 1450’s marks the early boundary of this period. For a time, the print trade catered to and coexisted with the traditional manuscript clientele. Thus, printed materials tended to be of scholarly subjects and were predominantly in Latin. But throughout this time there was a current of populist bookmaking that could be acquired by the average reader of the time. The Biblia Pauperum or “Bible of the Poor”, and a number of Donatus were produced with the poorly educated and illiterate in mind. Heavily illustrated using woodcuts, these books could be easily understood and were often used to dramatize the sermons of clerics and monks.

So, the tradition was in place, as the spread of printing swept over Europe, for an inexpensive product aimed at the “common folk”. Concurrently, more people were being educated in the basics of reading. Many children were given rudimentary reading instruction, and in some cases better that we give our children today as Latin and the Classics were also taught. Because of the growing competition between printing houses, materials were easier to acquire, for example it was said that every household along the small rivers and creeks in the Netherlands produced paper for the printing trade. Also, as print shops spread, the cost of publishing could be evened out by printing odd jobs in between major publications. This is not to say that an individual would strike it rich as a printer and publisher – Boom and Bust were a constant companion to the trade during this time.

All that was needed for the explosion of available reading materials was a vehicle of distribution to place books in the hands of the many. As is always the case, where there is a market, someone will fill the need, and for our story, we are introduced to the Chapman. Derived from Old English word ceap (‘barter, business, dealing’), the Chapman was a wandering seller of many diverse items. One of these items was the Chapbook.

Almost from the start of the Early Modern Period these little cheap books were produced by the thousands. Today considered tracts or pamphlets they were printed on cheap paper often using only a single sheet for the whole book. The sheet was then folded to make eight to twenty-four pages. They were rarely bound and were most often covered with a blank sheet of paper. Selling for about a penny they were affordable for most people and were read to the family or folks in the pub. From the mid-16th century production was especially heavy in Scotland and England where the appeal of the romantic or moral tale produced a steady following. But, it is precisely because of their flimsy construction and populist content that few have survived to this day.

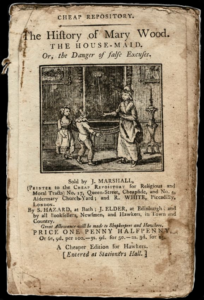

Our library has two examples from the late 18th and early 19th century. The first is from 1796 and is the moral tale of “The History of Mary Wood. The House-maid. Or, the Danger of false Excuses”.

Hanna More began publishing the “Cheap Repository of Moral and Religious Tracts” in 1795. She wanted to provide reading materials that were not of the low moral character of many of the chapbooks in circulation at the time. Between 1796 and 1817 more than 200 titles were published individually and reprinted as collected editions until the 1830. There were several printers and distributors including Samuel Hazard of Bath and John Marshall, located in Aldermary Churchyard, London.

Mr. Heartwell is the “Worthy Clergyman” of a country parish, he was sitting on his porch when he saw a figure running down the hill towards his house. “O fir, fave me! For pity’s sake hide me in you houfe”. He recognized her as Mary Wood the daughter of the Matthew Wood a now diseased parishioner. He had helped Mary by finding her employment as a maid with a well off family after her father died. He took Mary into the house and soon a large number of people came racing down the hill looking for Mary. Upon his inquiry Mr. Heartwell found that Mary was wanted for theft from her master’s house. Mr. Heartwell takes pity on her and through a number of different adventures Mary continues to find herself in trouble. Eventually Mr. Heartwell sends Mary a distance 50 miles away, to another clergyman, in hopes of finding better circumstances for her. But on the trip, she became weak eventually succumbed to her sickness.

Even though she repented in the end, for Mary Wood, the lying house-maid, death was “brought on by grief and shame at eighteen years of age, was the consequence of bad company, false promises and false excuses”. The tale concludes:

May all who read this story, learn to walk in the straight paths of truth. The way of duty is the way of safety. But “the wicked fleeth when no man pursueth, while the righteous is bold as a lion”.

It was hoped that Hanna More’s morality tale would provide encouragement for many who would follow Mary’s path, that they would learn from her folly and walk the higher path.

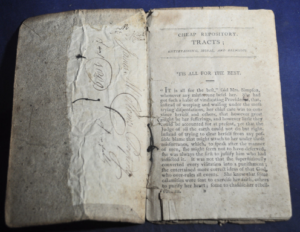

The second example is also from the “Cheap Repository” by Hanna More. Printed from a later edition, about 1800, it is the tale “ ‘Tis all for the Best ”. Following a similar narrative the protagonist falls from a high social position to that of a beggar.

Mrs. Simpson expired soon after, in a frame of mind which convinced her new friend that “God’s ways are not our ways.” But was left with her plea “Believe my dying words – ALL IS FOR THE BEST.

While contemporary analysis of this style of Chapbook is rather harsh, focusing on their perceived attempt to keep the lower classes in their place, one critic in the 1860’s noted:

We welcome the re-issue of both tales. Written at a time when it was necessary to counteract the exaggerated political aspirations set forth in the publications of the Jacobins and “levelers,” they may now serve to counteract the pernicious reading which we fear is in the hands of too many of our youth to-day, especially in the large towns. The book is tastily got up and well printed, and, with bright cover and neat illustrations, costs but a penny.

Worldcat: Link

- Title: The History of Mary Wood. The House-maid. Or, the Danger of false Excuses

- Publisher: Dublin : Sold by William Watson, and Son, No. 7, Capel-Street, Printers to the Cheap-Repository for Religious and Moral Tracts, And by the Booksellers, Chapmen and Hawkers, in Town and Country, [1797?]

- Language: English

- Setting: Early Modern Period, Britain

- DLWA Call Number: PR3605.M6 A6 1796a

Worldcat: Link

- Title: ‘Tis all for the Best

- Publisher: London, [1800?]

- Language: English

- Setting: Early Modern Period, Britain

- DLWA Call Number: PR3605.M6 A6 1800?