While looking at the great variety of bindings found in our stacks, I was thinking about the advent of the paperback book. In looking up the history of paperbacks I found that common knowledge would say that this style of book originated in the 1930’s with publications by Penguin Books. 1 But, as always, if you dig a little deeper the real story is quite different. It is recognized that Dime Novels, pamphlets and other ephemera were printed with paper covers in the 19th century. Even recognizing these publications preceded 1900, I found that the history of the paperback goes much further back. During the Late Medieval period, prior to the invention of the printing press, manuscripts were sold in an unbound form so that the purchaser could choose a binding of their own. Collections of books were often bound with the same style for a wealthy patron. This made their libraries personally distinctive. Printing and binding were separate industries. This custom was followed after the 1450’s with books made by the printing press. Sometime in the next 50 years printers covered the text block with paper to prevent the copy from being soiled by dirt and stains. While most books were bound with a hardback case binding there are examples throughout this period where books were bound with plain and decorative papers. Here are a few examples from our collection:

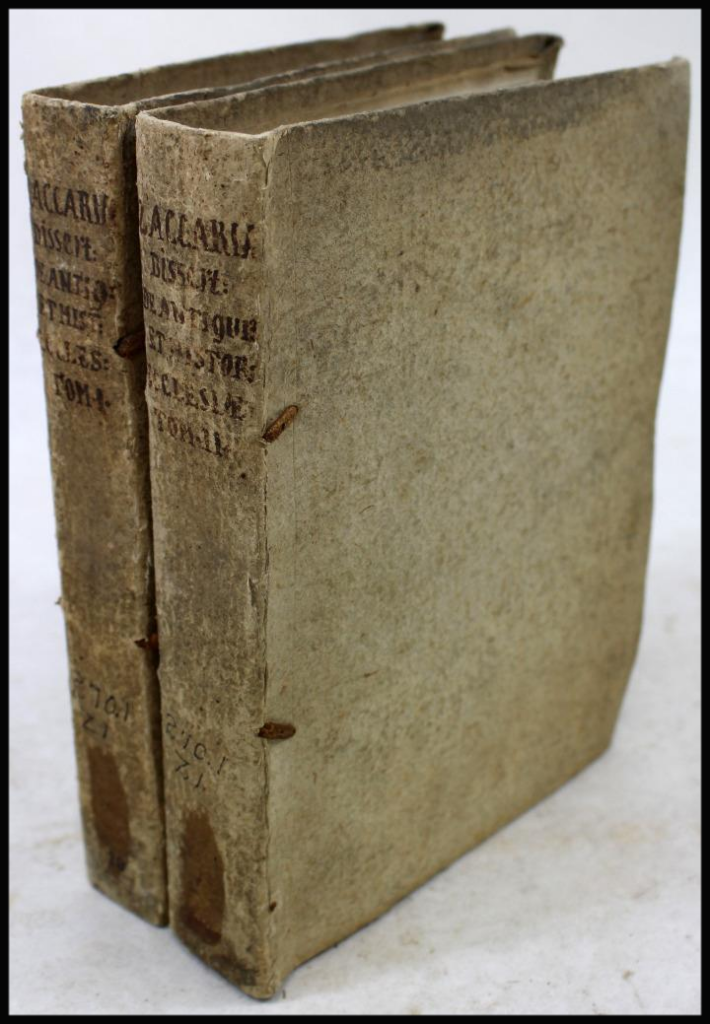

De Rebus Ad Historiam by Francesco Antonio Zaccaria, was published in 1781 and on the title page is found the imprint excudebat Pompejus Campana, Fulginiae. This two-volume work examines the topic of ancient church history. Both volumes can be found bound together, or individually, in vellum. It is also found in various forms of leather binding. Our library has the two volumes bound separately in a coarse, heavy paper.

Ensayo sobre la supremacía del Papa was published in Lima Peru in 1831 by José Masias for Jose Ignacio Moreno. Moreno argued for the supremacy of the Pope and the authority of Rome over all ecclesiastical affairs. This volume is bound with thick thread in a pamphlet style. It is interesting that this book came from the library of the noted Peruvian author Father Antonine Tibesar (1909-1992).

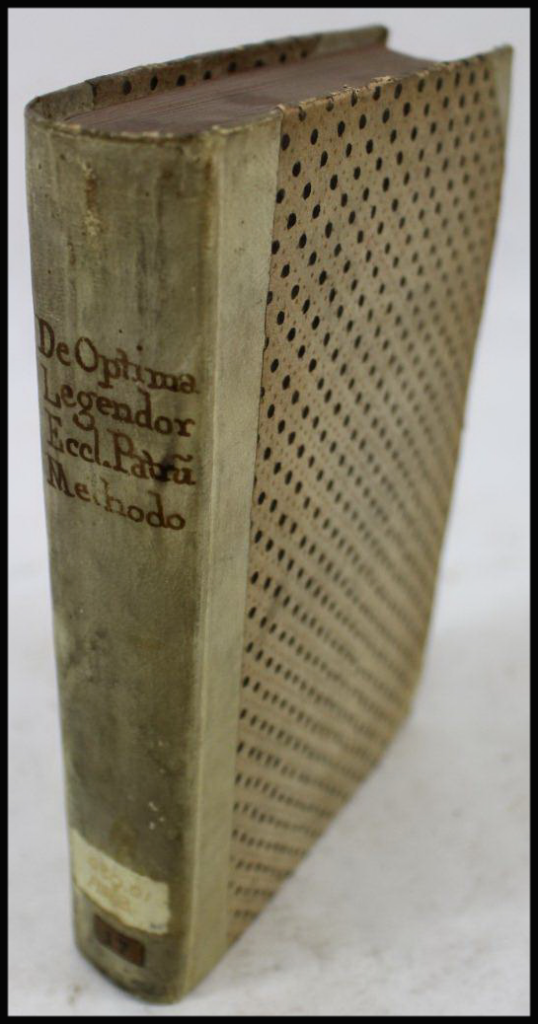

Our next example, De optima legendorum ecclesiae Patrum methodo was published in 1742 by ex typographia Regia, Augustae Taurinorum. Written by Bonaventure d’ Argonne this book provides a methodology for reading the Early Church Fathers. Here we see an intermediate type of binding with vellum on the spine and corners over a binding of decorated boards.

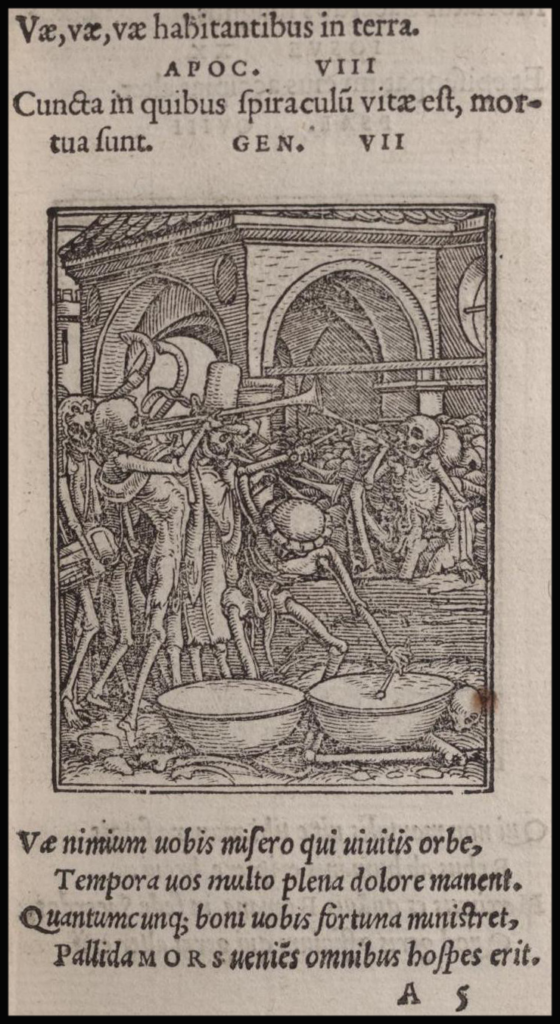

In the same tradition, the 1783 edition of Della Forza Della Fantasia Umana by Lodovico Antonio Muratori caries on the practice of vellum combined with printed paper. This book presents a bold theatrical representation of the celestial mechanics of imagination.

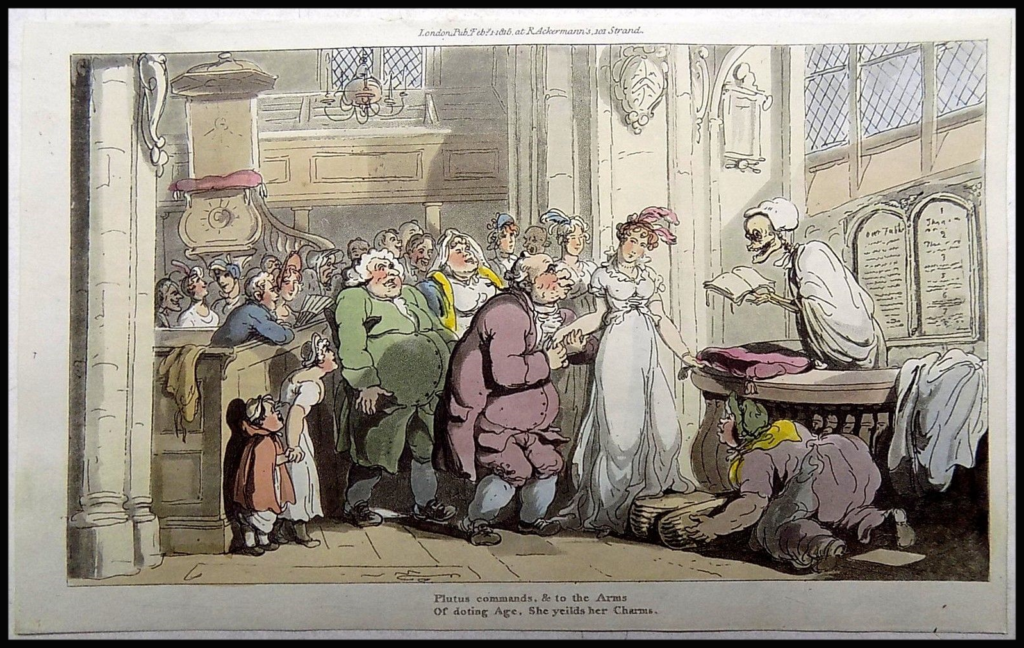

Finally, in this short survey of early bindings in our collection, is the 1830 book The romance of history: Spain printed in London and written by Joaquín Telesforo de Trueba y Cosío (1799?-1835). Here Joaquín provides a survey of the history of Spain from the Gothic Dynasty to the early 1800’s. In the same tradition of inexpensive bindings, we see a transition from paper and vellum to a low-cost cloth cover with paper titles.

Once we enter the 19th century a wide variety of bindings are used. Popular and inexpensive coverings of paper emerge. Where the majority of pre 19th bindings were sturdy leather and vellum the numbers of books bound with and paper prevail in the 20th century.

—–

DLWA Call Number: BR143 .Z13 1781 v.1 & v.2

Worldcat: Link – Volume 1

Worldcat: Link – Volume 2

- Title: De rebus ad historiam atque antiquitates ecclesiae pertinentibus dissertationes Latinae

- Author: Francesco Antonio Zaccaria

- Language: Latin

- Setting: Ecclesiastical history

DLWA Call Number: BX1810 .M67 1831

Worldcat: Link

- Title: Ensayo sobre la supremacía del Papa especialmente con respecto a la institución de los obispos

- Author: José Ignacio Moreno

- Language: Spanish

- Setting: Ecclesiastical history

DLWA Call Number: BR 67 .A74164 1742

Worldcat: Link

- Title: De optima legendorum ecclesiae Patrum methodo in quatuor Partes tributa

- Author: Bonaventure d’ Argonne

- Language: Latin

- Setting: Ecclesiastical history

DLWA Call Number: BF408 .M8 1783

Worldcat: Link

- Title: Della forza della fantasia umana

- Author: Ludovico Antonio Muratori

- Language: Italian

- Setting: Mind and body

DLWA Call Number: PR5699.T453 .R66 1830

Worldcat: Link

- Title: The romance of history : Spain

- Author: Joaquín Telesforo de Trueba y Cosío

- Language: English

- Setting: Spanish history

—–

–DLW