In 1548, the prominent London printer and bookseller Reyner (or Reginald) Wolfe undertook the project to produce a universal history and cosmography i.e. description and maps of the world. Other publishers, on the continent, had already produced such works with great success like the Liber Cronicarum by Hartmann Schedel and printed by Anton Koberger in 1493. After Wolfe’s death in 1573, his assistant Raphael Holinshed took over the project. He hired more writers and cut back the scope of the work to the British Isles. The Chronicles were first published in 1577 in a two-volume folio edition 1. As with other works of this type it was illustrated with numerous woodcuts making it a popular resource. After Holinshed’s death in 1580, Abraham Fleming published a significantly expanded and revised second edition in the years following 1587. This edition was produced in a large folio format, but this time without illustrations2.

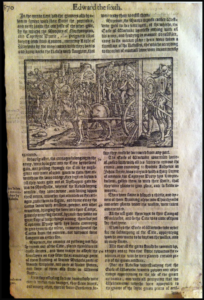

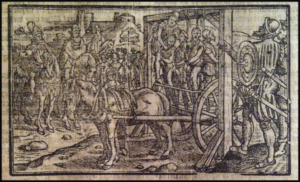

Holinshed’s Chronicles (1577) often referred to as just Holinshed is, in reality, a large collaborative work with content borrowed from many different authors. Its focus on describing England, Scotland, Ireland and their histories from their first inhabitation to the mid-16th century. The work was a principal source for many literary writers of the Renaissance, including Marlowe, Spenser, Daniel and Shakespeare3. Our library has several resources related to Holinshed. The oldest item we find in our collection is a leaf from the first edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles (1577). This fragment contains an account of Kett’s Rebellion where the Earl of Warwick defeats the rebels in 1549. The leaf is pages 1669(r) and 1670(v). It is a great example of the format and typology of early modern text production in England, and includes a woodcut depicting the execution of a group of rebels.

The second resource is Holinshed’s Chronicle: As Used In Shakespeare’s Plays, a classic Everyman’s Library (#800) work edited by Allardyce and Josephine Nicoll. Included are selections from The Chronicles where Shakespeare drew inspiration for his plays or copied in full sections for his dialogues. They point out that Shakespeare used the Holinshed edition of 1587 “for certain phrases in the former were repeated by him almost verbatim in several of his plays”4. While there are other works with extensive scholarly apparatus, the Nicolls’ provide an accessible resource on Shakespeare’s authorities.

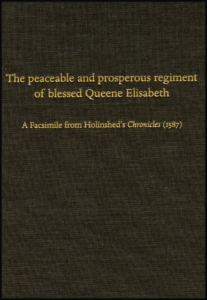

The last resource for Holinshed’s Chronicle, that we will highlight here, is The Peaceable and Prosperous Regiment of blessed Queene Elisabeth: A Facsimile from Holinshed’s Chronicles (1587) edited by Cyndia Susan Clegg and Randall McLeod. This volume includes extensive research into the way in which Holinshed’s Chronicle were censored by Elizabethan authorities and where large “chunks” 5 of the text were modified for political, religious and social reasons. This research relies heavily on the Huntington Melton copy of the chronicles, which consists almost entirely of proof sheets as well as copies from the British Library and Cambridge University Library. Clegg and McLeod provide a detailed reconstruction of the “castrated sheets” and their place in the final text of the second edition6. This work is also notable in that it sheds light into the edition used by Shakespeare.

The Peaceable and Prosperous Regiment of blessed Queene Elisabeth, 2005

These works are central to a number of disciplines ranging from the History of England, early modern print culture, and Shakespeare studies. Our library is fortunate to have access to these resources.

—–

DLWA Call Number: DA130 .H73 1577

Worldcat: Link

- Title: The firste volume of the Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande :.

- Author: Raphael Holinshed

- Language: English History

- Setting: Englans, Scotland and Ireland

DLWA Call Number: PR2955 .H7N5 1955

Worldcat: Link

- Title: Holinshed’s Chronicle as used in Shakespeare’s plays..

- Author: Raphael Holinshed; Allardyce Nicoll; Josephine Calina; W G Boswell-Stone

- Language: English

- Setting: Shakespear Studies

DLWA Call Number: DA350 .H65 2005

Worldcat: Link

-

- Title: Holinshed’s Chronicle as used in Shakespeare’s plays..

- Author: Raphael Holinshed; Cyndia Susan Clegg; Randall MacLeod

- Language: English

- Setting: Shakespear Studies, English History

—–

- The Oxford Handbook of Holinshed’s Chronicles. United Kingdom: OUP Oxford, 2013. pp. 5-12

- ibid

- ibid

- Holinshed, Raphael, Nicoll, Allardyce, Calina, Josephine, and Boswell-Stone, W. G. 1955. Holinshed’s Chronicle as Used in Shakespeare’s Plays. London Toronto: J.M. Dent & Sons, ltd. pp.vi.

- Review of The Peaceable and Prosperous Regiment of blessed Queene Elisabeth: A Facsimile from Holinshed’s Chronicles (1587). Renaissance Quarterly 60, no. 2 (2007): 647-649. p. 647.

- ibid

–DLW