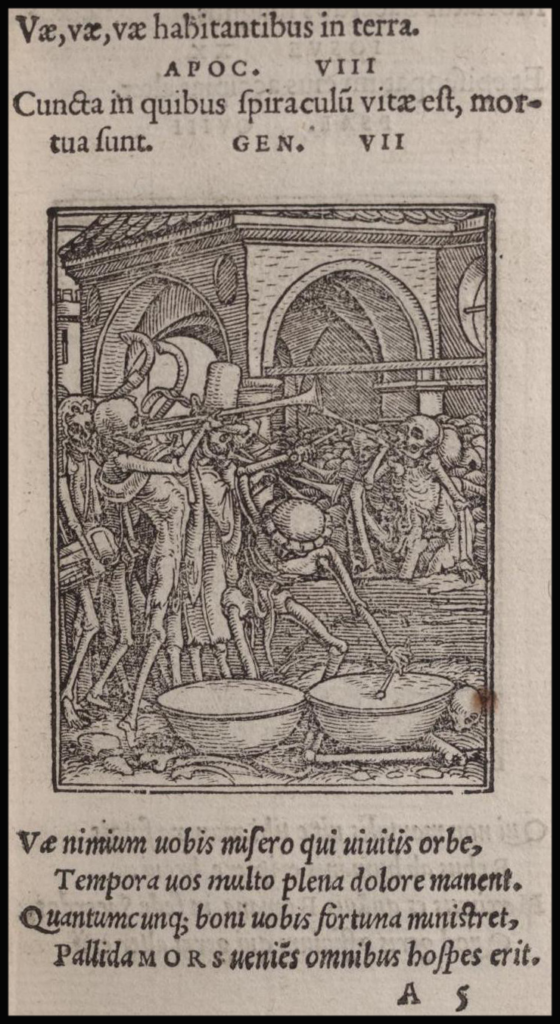

Control of information has been a battle since a stylus was first placed to clay tablet, knowledge is seen as power and a way to control people. There are large areas of human endeavor that have been lost because of purposeful behavior or carelessness. Throughout the ages, censorship is one of these acts that has shaped what we see today in our heritage of printed texts. Our topic today focuses on the censorship of books and pamphlets in seventeenth century Great Britain where texts deemed to be seditious were burned.

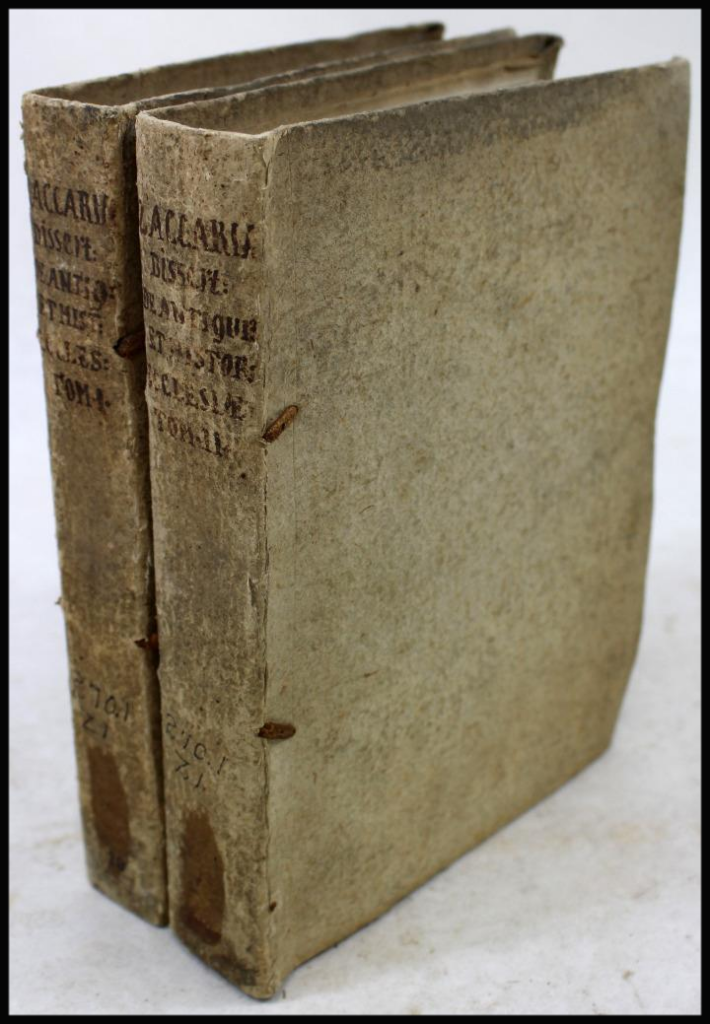

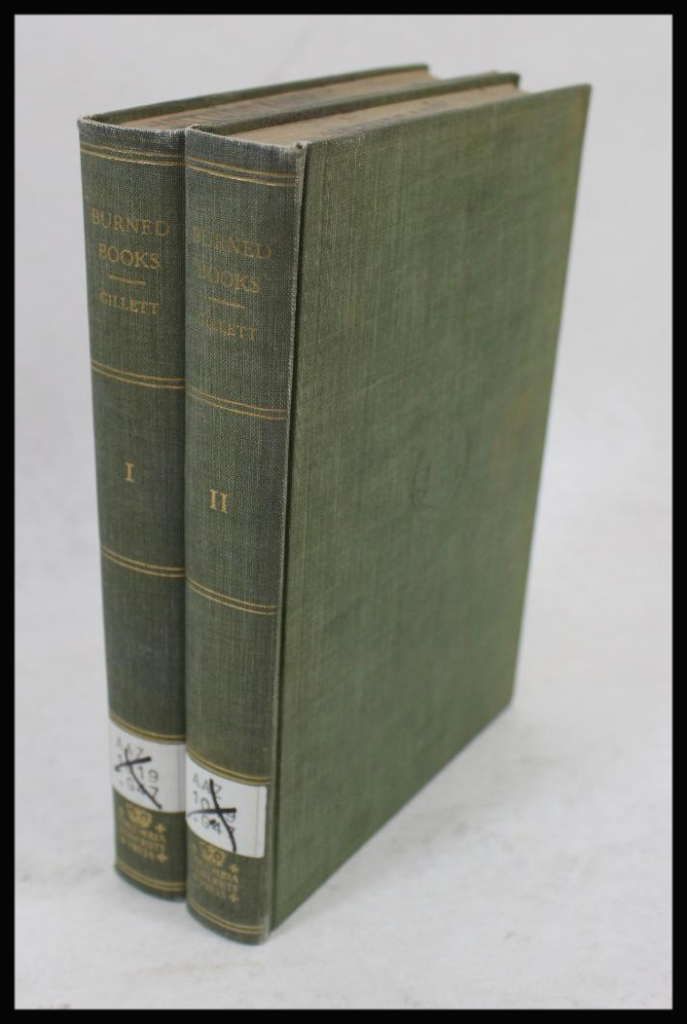

Charles Ripley Gillett (1898-1926) was librarian of the Union Theological Seminary in New York City. Through his work with the library collections and students he amassed a wealth of knowledge about the British book history. His two-volume set “Burned Books: neglected chapters in British history and literature”, catalogs hundreds of books that were condemned to be burnt at the demand of royal, parliamentary, ecclesiastical and local authorities. Gillett suggests, that, while there are many reasons for this censorship there are two circumstances where authorities resort to extreme measures to restrict the distribution of books and pamphlet.

Gillett’s first case was that when a, …civil government found its cornerstone threatened or its fundamental principles attacked, and, given the power, into the fire went either the rebel or his book. 1 Second, Gillett noted that When an …ecclesiastical establishment found its practice or its tenants attacked in writing or in a printed book, and, lacking the convincing scriptural authority on which it claimed to be founded, it had recourse to the argument of force, and the offending book was burned. The fiery trial was quicker than the course of protracted debate, and in controversy there is always the danger of defeat. 2

Given these observations, even though Gillett gives similar weight to works that are political and theological, he tends to focus more on the political realm rather than theological examples. For some this is welcome given his statement that one has difficulty in appreciating the sense of fear and apprehension with which multitudes in England and Scotland regarded the Church of Rome. 3 He goes on to state that It was due in part to dread concerning the danger in which the reformed faith was believed to stand, and also to the apprehension as to the effects of political ascendancy guided by a foreign power, 4 which we take to be the Church of Rome, France and other European powers.

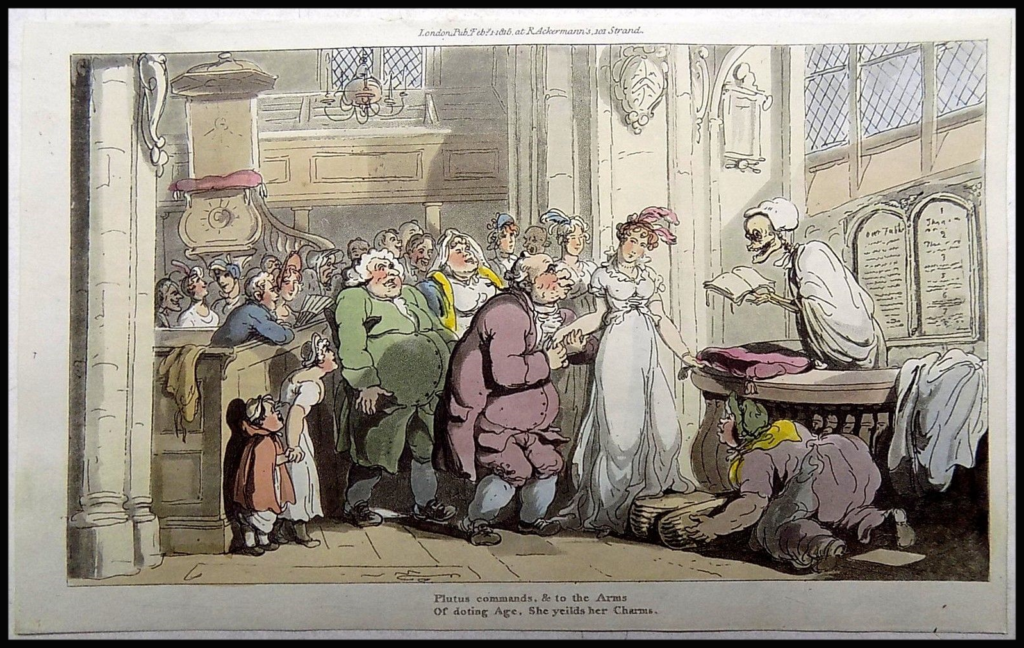

Gillett documents how the process played out once the decision had been made to prosecute the judgment of the authorities. Upon the confirmation of a proclamation the condemned books were gathered by the Usher of the House or by Wardens of the Stationers Company. Once they were gathered up, the books were given to the hangman of the local jurisdiction and a great fire was set. Official witnesses were assigned, and members of the crowd were often pressed into throwing the books into the fire. As a part of this ceremony the author was often present and forced to throw his books or pamphlets on the fire. Other times the author was locked in the pillory to experience his humiliation. But this was not always the end for the accused, many times the author was imprisoned or executed.

As to the effectiveness of the practice of burning books Gillett notes that the:

purpose to be achieved by burning an offending book was quite intelligible, though the procedure was far from intelligent. It was a lurid logic, but its premise was wrong and its conclusion was false. As an argument, fire has never been conclusive either in the case of a man or a book. 5

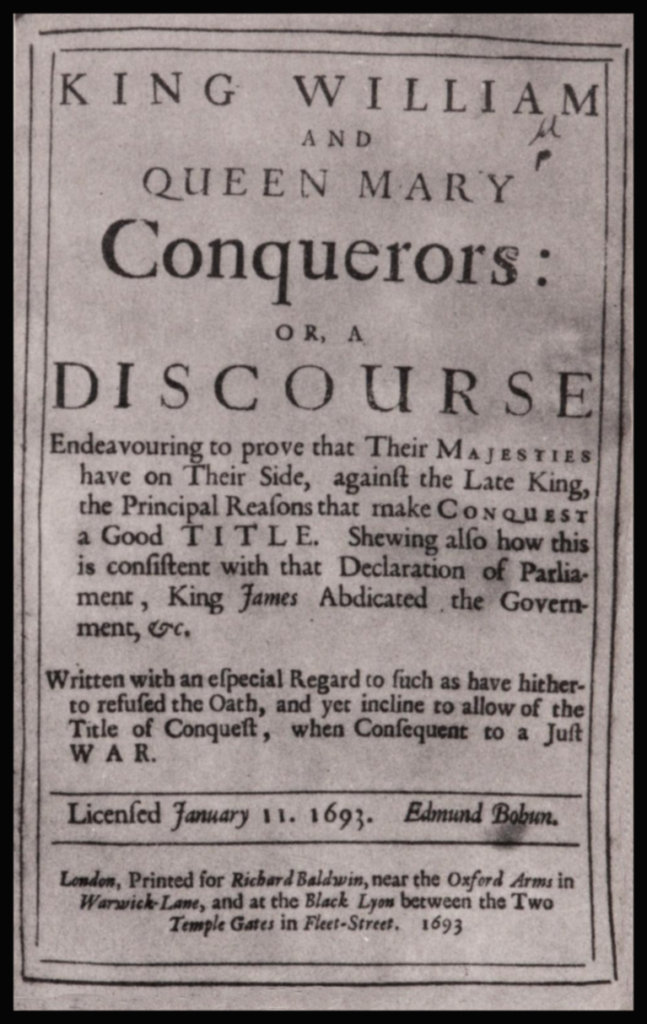

One interesting example, highlighted by Gillett, is the story of a pamphlet created, and published under a pseudonym, by Charles Blount (1654–1693) with the lengthily title of King William and Queen Mary, conquerors, or, A discourse endeavouring to prove that Their Majesties have on their side, against the late king, the principal reasons that make conquest a good title : shewing also how this is consistent with that declaration of Parliament, King James abdicated the government, &c. : written with an especial regard to such as have hitherto refused the oath, and yet incline to allow of the title of conquest, when consequent to a just war.. It was published in London and printed for Richard Baldwin in 1693.

Under the laws of the time the book was to be reviewed by the Licenser of the Press, a position that acted as a pre-publication censor. Edmund Bohun was a newly appoint “licenser” when he received this pamphlet for his scrutiny 6. Gillett suggests that this publication was a “trap for the licenser by a man who has a personal grudge to satisfy” 7. Using a purposeful sarcastic style, Blount argued in favor of William and Mary. Blount, was an English deist and a freethinking philosopher who was critical of the existing English order. His works were mostly credited to anonymous authors or written under a pseudonym Junius Brutus Philopatris.

Blount argued that William and Mary were, in fact, conquerors of England and the people should support them as their protectors. But it was written in a obscured manner thus it is no surprise that the pamphlet was licensed by Bohun. Nine days later there were more than 20 complaints 8 from the Commons and in 1695 Parliament undertook a sharp debate concerning the fate of the work and determined that it, too, should be burned by the common hangman. In the anticipated ironic twist, Bohun was fired from his new position.

Take a look at Gillett’s examination of book burning. This study will lay a foundation for an understanding of censorship in seventeenth century Britain but also pay attention to his pro Anglo-British and anti-European bias. In future posts we will explore other examples of research into censorship.

—–

DLWA Call Number: Z658.G7G54 1932

Worldcat: Link

- Title: Burned Books: neglected chapters in British history and literature

- Language: English

- Setting: Seventeenth Century British Censorship

—–

-

Charles Ripley Gillett : Burned Books: neglected chapters in British history and literature (Vol 1 4-9).

Date – 1814 - ibid

- ibid

- ibid

- ibid

-

Charles Ripley Gillett : Burned Books: neglected chapters in British history and literature (Vol 2; pp. 549-559).

Date – 1814 - ibid p.550

- ibid

–DLW