It is not only in our times that recycling is in vogue. In the early modern period with the rarity and expense of books, patrons frequently relied on the bookseller to take the responsibility of binding a text, often to match other volumes in their library. Needless to say, materials were expensive and relatively rare. Paper and vellum have always been one of the most expensive costs of manufacturing books, thus, little of it went to waste. Also, because of the process of printing, a lot of leftover, defective, or damaged printed material, called printers waste, was created. It was a common practice for bookbinders to collect sturdy parchment leaves from unwanted or outdated manuscripts and reuse those leaves as binding reinforcements or covers for their books. Scraps of paper were glued together to create an early form of cardboard for the structural parts of the binding process 1. The practice was so common that many books from the Medieval and Early Modern period have printers waste and manuscript fragments in their bindings. During the 19th and 20th century many of these artifacts were discarded as old binding were replaced with new.

This quote from Chrissie Perella sums up our surprise and amazement over the destruction of old books and manuscripts:

Manuscripts used as WHAT?!

Yes, Virginia, there is such a thing as ‘manuscript waste.’ To us, several hundred years later, it seems a horrible thing. However, it was common practice for early bookbinders to cut up and use pages from unwanted manuscripts as binding material. These pages were sturdy and were used for paste-downs, wrappers (covers), spine-linings, or gathering reinforcements. Not only did the practice essentially recycle texts that were outdated, damaged, or for some other reason, no longer used, it also gives us an opportunity to get a glimpse into the history of a specific text’s use. If we think about it, it’s not too much different than how we treat old newspapers today: as decoupage, potty-training mats for puppies, packing material, etc., etc., etc 2.

More recently, scholars have begun to recognize the value of these materials and a new field of study, Fragmentology, is emerging 3. Researchers are canvassing their stacks and valuable unknown or lost ancient texts have been found. For example, one of the more important recent finds is the The Archimedes Palimpsest 4, that contained works that were only known by references in other ancient documents. Because of the new study of binding fragments there have been important biblical, Islamic and Hebraic texts discovered in recent years.

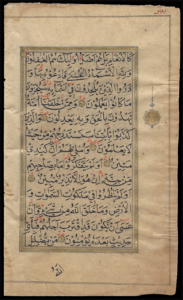

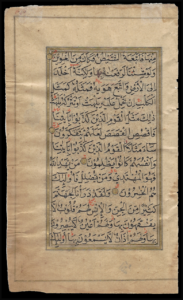

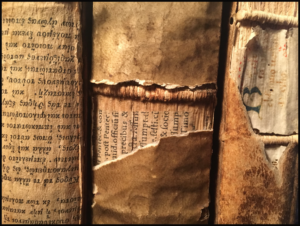

Given the above, a brief look into the stacks of our library is in order. First we have a number of manuscript fragments removed from some mid 15th century German bindings. Most of these are probably dated around 1425 to 1450 although one of the fragments (the largest, rectangular fragment on the right) might be earlier as it appears to be a palimpsest with a trace of Carolingian script dating to about c1100 AD.

Early Medieval Manuscript Binding Fragments.

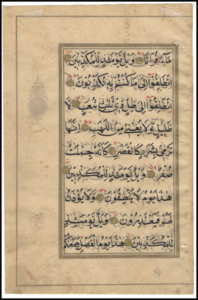

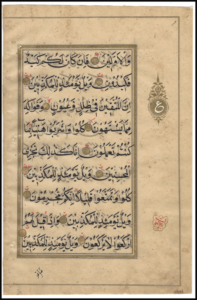

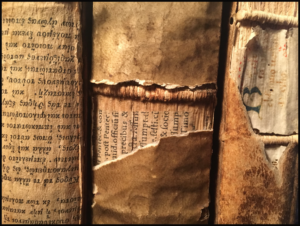

Second are a set of three volumes that show different types of binders waste in use: a page, with a Greek font, using scrap from the same production run, for spine reinforcement. This example is from books printed in 18th century using more modern mechanical printing press; next a book from the 17th century where a waste leaf from an older book is used between the bands to reinforce the cover attachment; and finally a 16th printed book has strips of an earlier handwritten and rubricated manuscript cut into strips for use in reinforcing and attaching the cover.

Three examples of different Binders Waste use.

We have many more examples in our Manuscripts and Archives, none so spectacular as the Archimedes Palimpsest, but there a a gold mine of information hidden under the covers.

—–

DLWA Call Number: AC1 DC707 M1450 01

Worldcat: Link

-

- Title: Medieval manuscript binding fragments.

- Author: Anonymous

- Language: Latin, Unknown

- Setting: Book Binding

—–

- Specific references for this study are difficult to pinpoint as the analysis of “Binders Waste” and “Manuscript Fragments” was not considered as a ligitimate field of study. Resources for this section were gleaned from a number of small reports on the web.

- Fugitive Leaves : Chrissie Perella

- See the Fragmentarium : Laboratory for Medieval Manuscript Fragments as one example of this research.

- The Archimedes Palimpsest

–DLW